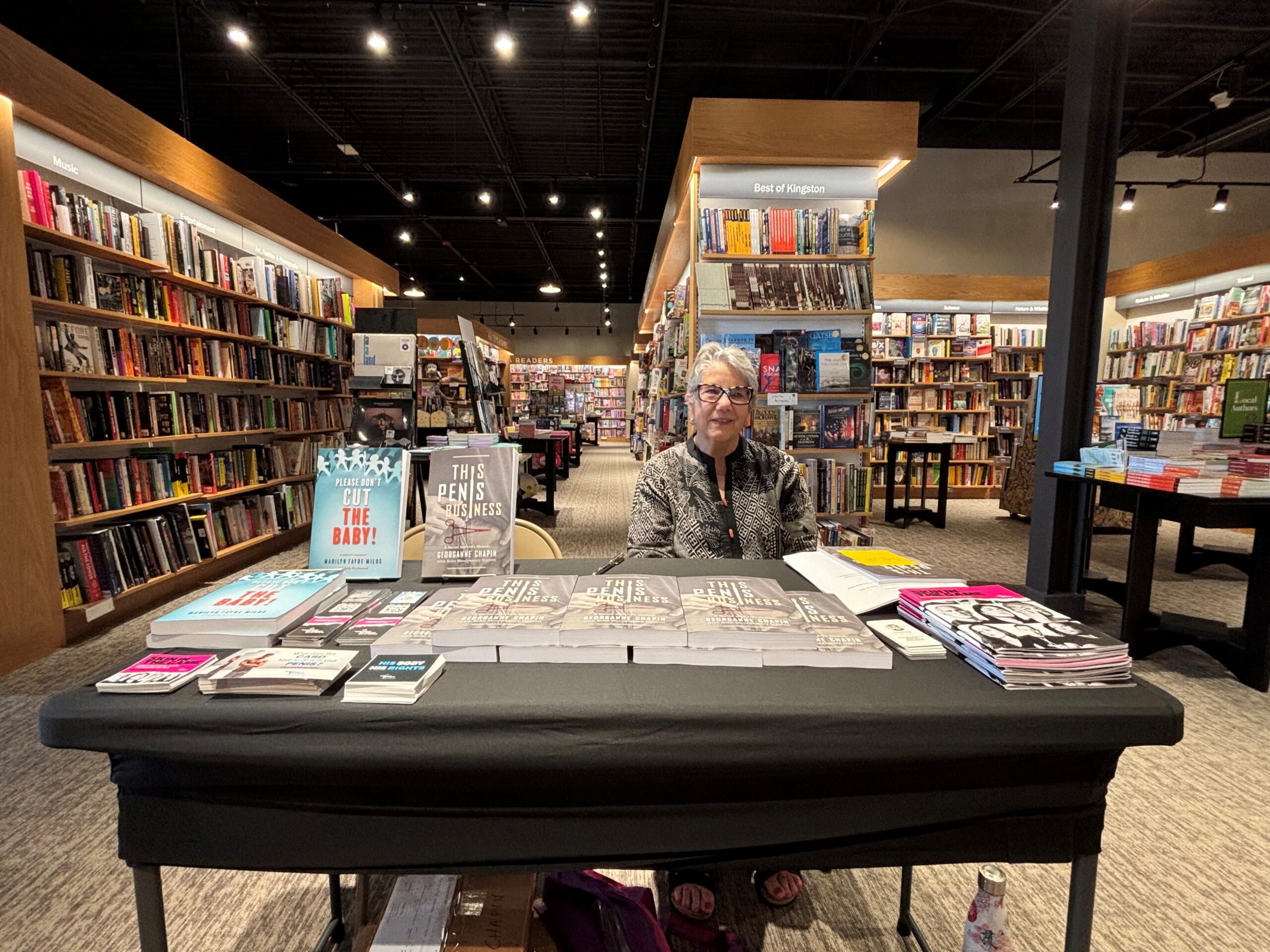

“One Happy Family”, drawn by Robert Johnson

Several years ago a young Hispanic couple moved into temporary housing in our neighbors’ basement in Northern Virginia. Neither my wife nor I had a chance to speak to the couple in the first few days after they moved in, but one morning I noticed that the very pregnant young woman was leaning against their pick-up truck across the street, holding her bulging abdomen as if fearful she might give birth any moment. I decided to introduce myself and asked if she was having a boy or girl. She looked at me sadly and said, “A BOY!” I said “Wonderful! Are you going to have him in a hospital?” She looked at me desperately. “Yes, but I worry because they want him circumcised. My mother says ‘No!’ And I don’t want it too. But nurses at the hospital keep saying ‘He is in America now! You should let a doctor circumcise him to keep him healthy and be like American boys.'”

“You are right to say ‘No!'” I said. “It isn’t necessary to circumcise him and it is harmful. The hospital people are wrong.”

“I would have him with my mother’s help in her trailer,” she said, “but he is so big I worry if there could be a problem with birth!”

“Well, the hospital has to get your informed consent to circumcise. You have the right to say ‘No.’ No one can make you say ‘Yes.’ And circumcision will harm your baby. I know because I’m circumcised and it harmed me. If you could wait a minute, I can get you some information to show the hospital that you have the right to say ‘No!'”

I ran into our house, turned on my computer, looked up Intact America, and found a statement in both English and Spanish explaining that circumcision is unnecessary and harmful to a baby and mustn’t be performed without the parents’ informed consent. I printed the statement, dashed across the street, and gave it to the woman. She read the Spanish version eagerly and said, “Thank you! I will show it to my mother and take this to hospital. Gracias!” She took the paper, eased herself into the driver’s seat, and drove off.

For several days I didn’t see either the woman or her husband. Then one morning I noticed the familiar truck parking across the street. Eager for news, I rushed outside. The young woman, much thinner now, opened the passenger door and got out carrying a large, healthy-looking baby boy. Before I said a word, a short, older woman, who turned out to be the young woman’s mother, scurried around her daughter, beaming, and said, “Thank you, sir! My grandbaby is happy baby boy!” The young mother also thanked me and added, “At hospital they ask me ‘Are you SUUURE you don’t want him circumcised?’ I said, ‘Yes! I am sure!’ They ask this NINE TIMES! And I say, ‘Yes, I am sure!’ nine times. And when we show them the paper you gave me they at last agree not to circumcise my big little boy.” As the mother, grandmother, and baby got back in the truck, I noticed the woman’s husband giving me a thumbs-up and a smile before the family drove off.

I never saw this family again. I learned the next day that they had moved to another temporary home in a different part of the county. Knowing the baby was born in an American hospital and that to some degree my own intervention helped prevent his being circumcised made me happy for a while, but not so happy as to prevent an all-too-familiar, deeper, darker feeling from nudging its way back into consciousness.

I was not so lucky when I was born in Methodist Hospital in Peoria, Illinois in 1945. My father, who knew very well that my mother might be giving birth to a baby boy within a few days, decided to go on a “business trip” to Milwaukee, Wisconsin instead of playing an important supportive role on my mother’s and my behalf. Years later, my mother told me she “never forgave” him for leaving her, forcing her to depend on a neighbor to take her to the hospital when it was time for me to be born. Four years earlier, he’d taken her to the hospital when my brother was born, so why did my father go on a needless business trip on the important occasion of my birth? As it happened, I was born at 3:30 in the morning from a sedated mother, “attended to” by a doctor, then whisked away to a maternity ward. As far as I know, the attending doctor circumcised me that very night, bandaged me up, and sent me to a maternity ward to cry myself to sleep… if I slept at all.

I would say I have no conscious memory of that night, but that is not entirely true. Sixty years later, while practicing primal therapy exercises on my own at home, part of a decades-long quest to uncover the sources of life-long feelings of anxiety, inadequacy, depression, terror, and rage, I suddenly felt a sharp cutting sensation around the shaft of my penis. I stopped the exercise immediately as I realized the sensation was my body’s way of telling me that I was re-experiencing my infant circumcision in 1945.

Why had my father, who was born in rural Indiana in 1907 and left intact, chosen to be away on a “business trip” rather than to take steps to protect me from the circumcision that, without strong intervention, was sure to happen to me after I was born in 1945? I could only guess, since my father was no longer living, that it was because he was caught off guard when my older brother was circumcised in a hospital four years earlier. My father was a first-born child when he was born and always seemed, like many fathers of his era, to place special concern on the welfare of his first-born son. I may be wrong, but I strongly suspect he couldn’t allow his second-born son, by NOT being circumcised, to have an advantage in life over his first-born son. Could this explain his mysterious decision to go on a “business trip” at this special time?

Of course, I’ll never know for sure, but I do believe that was the case, and I suspect that my strong feelings about the wrongness of allowing an infant boy to be traumatized and sexually wounded by circumcision may be what prompted me to run out of my family’s house toward a distressed, very pregnant stranger to do whatever I could to help a baby boy have a happier life than mine had been.

— Robert Clover Johnson

Interested in lending your voice? Send us an email, giving us a brief summary of what you would like to write about, and we will get back to you.

Vinthou

September 24, 2021 9:40 amWhat a great story! Helping to keep baby boys whole is so therapeutic. Good for you!

Also, I’m very sorry that no one was there to protect you when you were born. Much to my distress, the same happened to me. Far too much trust was placed in the medical profession back then.