The practice of circumcision, a surgical procedure to remove the foreskin of the penis, has been a topic of intense debate and discussion. This article aims to provide a comprehensive timeline-based perspective on the physical and psychological impacts of circumcision on boys, emphasizing the importance of understanding their experiences in greater detail.

Pre-Circumcision: The Anticipation Phase

In the days preceding circumcision, families often experience a wide range of emotions due, for instance, to indecision over the choice to circumcise or guilt at having made that decision (to protect your child, specify not to circumcise in your birth plan checklist). In the case of religious circumcision, families may be stressed by various practical preparations as well as anxiety over the cutting of their baby boy. The child, oblivious to the impending procedure, might pick up on the heightened anxiety or solemnity permeating their surroundings.

“A study published in the “Journal of Clinical Nursing” found that many parents experience significant anxiety and uncertainty when making the decision about circumcision for their child. This study highlights the emotional burden on parents, who often feel pressured to make a quick decision shortly after birth.” (“Parental decision-making about neonatal circumcision in the United States,” Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2018)

This phase can magnify any dissension in the family or parental unit regarding circumcision. It is wise to acknowledge and address the emotional dynamics that arise during this period, as they can impact the well-being of the family unit both short- and long-term.

The Circumcision Procedure: Day of the Surgery

On the day of the surgery, the child is taken from his mother or father early in the morning, having been fed two hours earlier to ensure the baby won’t choke on undigested milk or formula during the circumcision. An invasive process that most often involves pinching the sensitive foreskin with hemostats and a scalpel or scissor, the immediate impact on the child is two-fold: physical pain and the psychological shock that accompanies any surgical intervention. Circumcision is not always performed with some form of analgesia to lessen the pain. However, even when it is, there is still discomfort and distress for the infant or child, especially if strapped down to ensure immobility. Additionally, the psychological impact of leaving the warmth and comfort of the parent’s arms and undergoing surgery at a young age can cause overwhelming anxiety and stress.

A study published in “Pediatrics” found that over half of the circumcisions in the U.S. might be performed without adequate analgesia. It emphasizes the importance of effective pain management in these procedures. ( “Pain and Its Effects on the Human Neonate and Fetus,” Pediatrics, 1987)

Post-Circumcision: The Immediate Aftermath (First Week)

The first week following circumcision is a critical period for the child’s well-being. During this time, the child may experience acute pain, particularly during urination, as the urine makes contact with the wound. Parents must know the proper way to dress the wound and to keep it away from contact with urine or the chafing of the diaper. The child may exhibit signs of distress, such as crying and discomfort, making this period traumatic for both the child and the family witnessing the child’s distress. Parents should receive not only an at-home care sheet on how to care for the circumcision wound but also be trained to look for signs of infection (redness, swelling, or fever) and other distress. They should have a phone number to call with any concerns.

Second and Third Week After Circumcision

During the second and third weeks, the physical pain gradually subsides as the healing continues. However, it’s worth noting that the wound’s sensitivity may persist, leading to occasional discomfort, especially during activities such as diaper changes or baths.

Post-Circumcision: Early Recovery (One Month After)

One month after circumcision, most physical wounds have healed, but it is important to acknowledge the potential risk of complications, such as the continued risk of infection or improper healing. The one-month doctor visit is paramount in ascertaining that the circumcision was performed properly, with no disfigurement as a result of the surgery or healing. . Unfortunately, this post-circumcision period often goes unmonitored, as many mistakenly assume that the absence of visible complications indicates complete recovery. By shedding light on the ongoing recovery process and emphasizing the need for continued vigilance during this phase, we can foster a more comprehensive understanding of post-circumcision care and ensure the child’s well-being.

Long-Term Physical and Psychological Effects

- The long-term effects of circumcision manifest over the years.1 Year After: At this stage, the child’s physical health may appear normal, but subtle impacts, such as sensitivity or irritation, may persist. Exploring these nuances can help in understanding any potential long-lasting physical consequences.

- 5 Years After: Psychological and emotional effects may surface as the child ages. These can include questions about body image, self-perception, and autonomy. Delving deeper into these aspects can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the potential psychological impacts in the long run.

- 10 Years After: The impact on sexual health and personal identity becomes more apparent as the child approaches adolescence. At this stage, the boy may start to understand and question the implications of the procedure he underwent as an infant. Examining the evolving perceptions and thoughts of the child as they navigate their developing identity can shed light on the long-term psychological impact.

Advocacy, Support, and Policy Change

It is vital that parents who decide to circumcise their child are as informed and educated as parents who choose not to circumcise their child so that they can advocate for their child if there is any kind of complication during or post-circumcision.

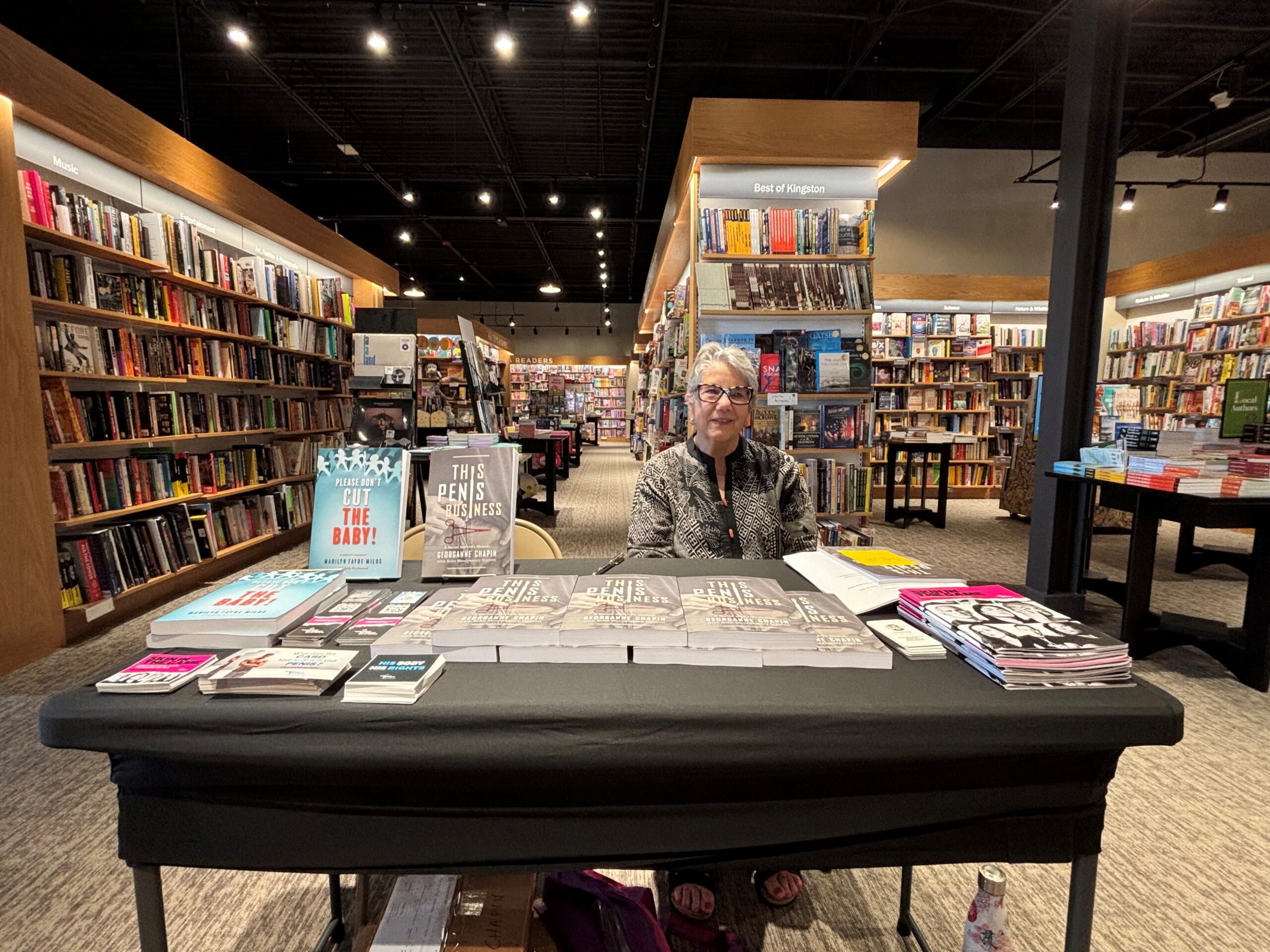

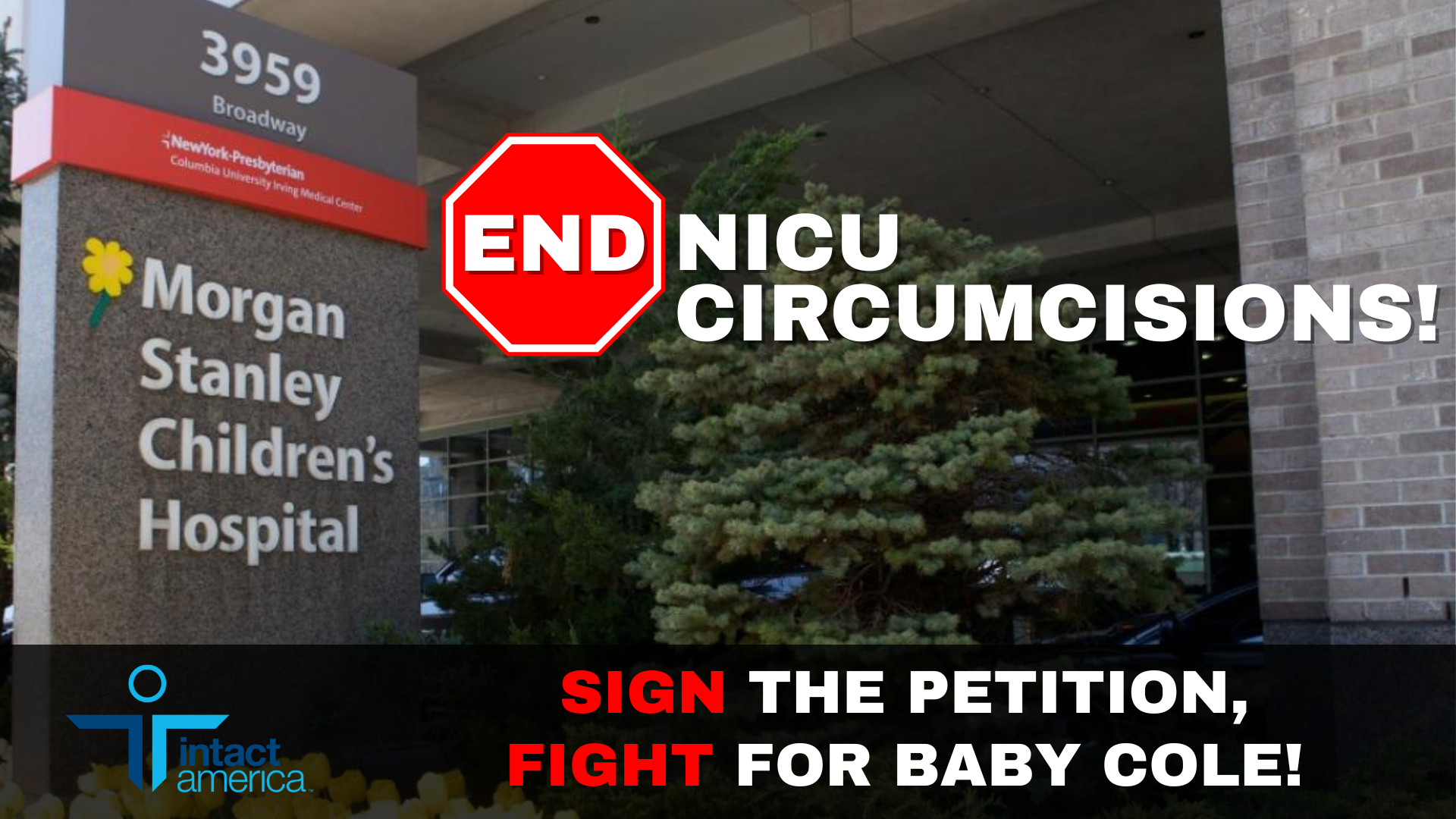

In response to growing concerns about the impacts of circumcision, including potential physical and psychological effects, anti-circumcision movements have gained significant momentum. These movements advocate for the principles of bodily autonomy and informed consent, emphasizing the importance of personal choice regarding one’s body.

As awareness has increased, support networks for individuals affected by circumcision have emerged, providing a safe and empathetic space for sharing experiences, seeking guidance, and fostering healing. These networks are crucial in promoting understanding and solidarity among those who have undergone the procedure or are considering their options.

Moreover, there has been a notable push towards reevaluating the legal and policy frameworks surrounding circumcision. Advocates challenge the normalization of circumcision and instead promote a rights-based approach to child health. The aim is to ensure that decisions regarding circumcision are made in the best interest of the child, taking into account the principles of bodily autonomy, informed consent, and medical ethics.

By expanding on the various advocacy efforts and policy debates surrounding circumcision, we can deepen the discussion on the larger societal implications. This includes examining the cultural, ethical, and human rights dimensions and considering alternative practices and approaches to addressing health concerns. Such discussions pave the way for informed decision-making, improved healthcare practices, and a more comprehensive understanding of the complex issues involved.

Final Notes on Circumcision Suffering Timelines

The journey of a child through circumcision is an intricate and multifaceted process, encompassing a wide range of factors and experiences. It involves not only the physical act of the procedure itself but also the emotional and psychological aspects that come with it.

When examining the timeline of experiences in greater detail, we gain a deeper understanding of the short-term and long-term impacts of circumcision. From the initial decision-making process to the actual procedure and post-operative care, each stage plays a crucial role in shaping the child’s well-being and future.

Society must question traditional practices surrounding circumcision and advocate for informed choices. By prioritizing the well-being and autonomy of the child, we can ensure that decisions made regarding this procedure are made in their best interest. This involves considering factors such as their individual needs, cultural beliefs, and medical evidence.

By delving into the intricacies of circumcision, we can foster a more comprehensive and informed dialogue surrounding this topic. This includes exploring alternative practices, discussing potential risks, and promoting open conversations considering individuals’ and communities’ diverse perspectives and experiences.

In doing so, we can move towards a more holistic understanding of circumcision, paving the way for respectful and informed decision-making that respects the rights and well-being of the child.

Christine Cleary

November 18, 2024 2:12 pmAs a parent educator I have taught about the dangers of circumcision for more than 30 years, the rates seem to eb and flow but the casual acceptance of this procedure is such a huge problem. Thank you for the work you do to educate.